Swapping Spheres of Influence

US, China, Russia, and NATO walk into a bar...

After a very disjointed December of holiday activities, I find myself finally back into a normal, and welcomed, routine.

If you had ‘Silver’ and ‘Venezuela’ on your market bingo cards to start the year, firstly, well done, and secondly, please tell me how you knew. It has been quite the unexpected turn of events.

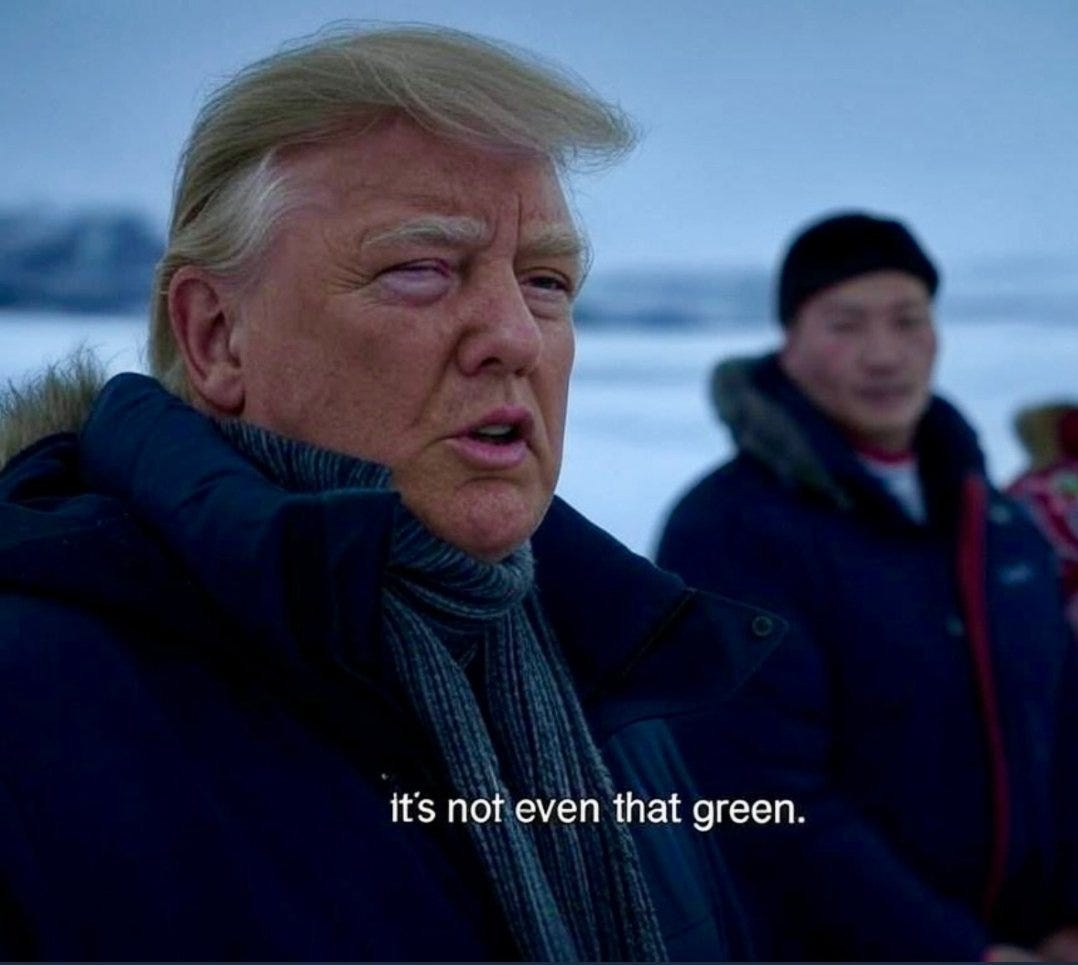

It’s reasonable to question what this all leads to. Trump’s delight at the early and swift success of his Venezuela operations has surely tingled his appetite for more. The target is already apparent. The quiet child named Greenland now finds itself in a custody battle between its parent, Denmark, and a distant relative, the US, who has no fundamental right to be in the picture.

Trump’s ideologies on Greenland are not new to the Trump 2.0 regime. They first appeared in 2019. The premise of Trump’s reasoning that he can and will take control of Greenland stems from the Monroe Doctrine (recently dubbed the ‘Donroe Doctrine’ by Don himself).

The Monroe Doctrine is a US foreign policy from 1823 warning European powers against further colonisation or interference in the Americas, establishing separate spheres of influence and asserting US opposition to new European control in the Western Hemisphere. In exchange, the US pledged non-interference in European affairs. I could argue that Trump’s interference between Russia and Ukraine already violates the latter part of the agreement, but I am no geopol expert.

Canada and Panama also fall into Trump’s field of vision. Maybe they are next on the list. But what happened in Venezuela over the weekend has really made this a closing reality.

Regardless, officials in Copenhagen are no longer treating Washington’s rhetoric as abstract. That shift in tone was reflected bluntly by Denmark’s prime minister, Mette Frederiksen, who warned on Monday that any US move against Greenland would not simply be a bilateral dispute, but a structural rupture. An attack, she said, would spell the end of Nato and of the security architecture that has underpinned the West since the Second World War.

Europe’s largest capitals moved quickly to reinforce the point. In a joint statement on Tuesday, leaders from France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, the UK and Denmark described the Arctic as a “critical pillar” of European, international and transatlantic security. The message to Washington was direct: the region is not a peripheral theatre, and any attempt to reshape it would have to be done with allies, not over their heads.

I think most would agree that an outright military takeover of Greenland is completely doable but highly unlikely. A slightly more plausible outcome might be the US persuading the people of Greenland, only 57,000 of them, to vote for independance. That wouldn’t cost the US an awful lot and then opens the doors for more military operations in the Artic.

Either way, expect relations between the US and Europe/NATO to diminish. Where more concern may lie is with Russia and China.

Both Moscow and Beijing moved quickly to condemn the removal of Nicolás Maduro. The statements were predictable. Less so is the degree to which Venezuela itself really matters.

For China, Caracas is now a leverage. If presented with a credible trade-off that secured Beijing a freer hand over Taiwan, it is difficult to argue that Chinese influence in Venezuela would rank as anything more than expendable. Russia’s math is similar. Its objections are loud, but its priorities lie much closer to home. If Ukraine were on the table, Venezuela would not be.

Trump may genuinely believe that a world organised into informal spheres of influence offers a path back to what the latest US national security strategy calls “strategic stability” with both Russia and China. It is an old idea, and it carries a certain surface logic: fewer overlapping claims, fewer points of friction, fewer reasons for confrontation.

The problem is that it assumes away the interests of those deemed too small to matter. Spheres of influence are, by definition, arrangements made over the heads of smaller states. But those states retain agency. They do not simply dissolve into geography. Ukraine’s experience is a reminder that countries assigned to someone else’s orbit do not always accept the role. They’ve put up a good fight so far.

Even if one brackets that inconvenient reality, the great-power case for spheres of influence is weaker than it first appears. The US does not, and cannot, confine its interests to a single hemisphere. China may define Taiwan as a “core” national interest, but Washington sees the island’s semiconductor dominance (and the shipping lanes of the South China Sea) as directly tied to its own security and economic position. Influence, once globalised, is not easily regionalised again.

Which is why any clean swap — American primacy in the western hemisphere in exchange for Chinese primacy in east Asia — would indeed be a deal of the century… for China.

Time for my coffee.

J